When working with microservices at scale, performance optimization becomes crucial for maintaining both system reliability and cost efficiency. Getting visibility into how your Go services behave under load is the first step towards making them faster and more efficient. This post will guide you through setting up essential observability tools: metrics and profiling. While the examples will be specific to Go, the concepts apply to other languages as well.

💡 If you want to follow along, you will need to have Go installed: https://go.dev/doc/install.

Metrics: Your Service’s Dashboard Gauges #

Think of metrics as the dashboard gauges for your application. They provide quantifiable measurements of your service’s health and performance over time, like request rates, error counts, latency distributions, and resource utilization (CPU, memory). Starting with metrics gives you a high-level overview, helps identify trends, and allows you to set up alerts for abnormal behavior.

Runtime metrics can be easily added using Prometheus, a popular open-source monitoring and alerting toolkit. You can install the Go client library by running:

go get github.com/prometheus/client_golang

After that, adding a basic set of Go runtime metrics (like garbage collection stats, goroutine counts, memory usage) is as simple as exposing an HTTP endpoint using the default promhttp.Handler:

package main

import (

"log"

"math/rand"

"net/http"

"time"

// Import pprof package for side effects: registers HTTP handlers.

// We use the blank identifier _ because we only need the side effects (handler registration)

// from its init() function, not any functions directly from the package.

_ "net/http/pprof"

)

func main() {

// Start the pprof HTTP server on a separate port and goroutine.

// Running it in a separate goroutine ensures it doesn't block the main application logic.

// Using a different port (e.g., 6060) is common practice to avoid interfering

// with the main application's port (e.g., 8080).

go func() {

log.Println("Starting pprof server on localhost:6060")

log.Println(http.ListenAndServe("localhost:6060", nil))

}()

// Your main service logic would go here...

// For demonstration, we'll randomly pick a number every 100ms

log.Println("Main application running...")

for {

log.Println(rand.Intn(100))

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

}

}You can run this example with go run .. Metrics will now be available at localhost:8080/metrics.

💡 Tip: In a real setup, you wouldn’t typically access this endpoint directly in your browser. Instead, a Prometheus server would periodically scrape this endpoint, storing the time-series data. You’d then use tools like Grafana to query Prometheus and visualize the metrics. However, checking the

/metricsendpoint manually is a great way for quickly verifying that your application is exposing metrics as expected, especially when adding custom ones.

Adding More Detailed Metrics with Prometheus #

The default handler is a good start, but often you’ll want more detailed information about your application code or the Go process itself. The collectors package provides fine-grained metrics about the Go runtime and the process.

Here’s how you can create a custom registry and add these specific collectors:

package main

import (

"log"

"net/http"

"github.com/prometheus/client_golang/prometheus"

"github.com/prometheus/client_golang/prometheus/collectors"

"github.com/prometheus/client_golang/prometheus/promhttp"

)

func main() {

// Create a non-global registry.

reg := prometheus.NewRegistry()

// Add collectors for Go runtime stats and process stats.

// TODO: check if this can be done more easily

reg.MustRegister(

collectors.NewGoCollector(),

collectors.NewProcessCollector(collectors.ProcessCollectorOpts{}),

)

// Expose metrics using the custom registry.

http.Handle("/metrics", promhttp.HandlerFor(reg, promhttp.HandlerOpts{}))

log.Println("Starting server on :8080")

log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil))

}This setup gives you deeper insights into Garbage Collector (GC) performance, memory allocation details, and process-level stats like CPU and memory usage, file descriptors, etc. Beyond these, you can easily add your own custom application-specific metrics (e.g., number of cache hits, specific business operation counters).

For a complete example of runtime metrics collection, see the prometheus/client_golang example.

Profiling: Finding the Needles in the Haystack #

While metrics give us a great overview (the “what”), they often don’t tell us the “why.” If your latency is high or CPU usage is spiking, metrics alone might not pinpoint the exact lines of code responsible. Their granularity is usually too low for deep optimization. This is where profiling comes in – it helps us look inside the application’s execution to see exactly where time is spent or memory is allocated, revealing the bottlenecks.

Profiling Fundamentals #

Profiling captures detailed runtime behavior. For performance optimization, two types are most commonly used:

- CPU Profiling: Captures stack traces over time to show where your program is spending its CPU cycles. Essential for identifying “hot paths” – functions that consume significant processing time.

- Memory Profiling: Takes snapshots of the heap to show where memory is being allocated. Helps understand object lifetimes, identify memory leaks, and analyze garbage collection pressure. Understanding allocation patterns is key to performance in Go.

Go also provides specialized profiles (goroutine, block, mutex), which are useful for diagnosing concurrency issues but are generally used less frequently than CPU and memory profiling for general optimization.

Local Profiling with pprof #

Go’s built-in pprof package makes profiling straightforward. It can collect profiling data and expose it over an HTTP endpoint for analysis.

Local profiling with pprof is invaluable during the development cycle and for investigating specific, reproducible performance issues. It’s the go-to tool when you need immediate feedback on the performance impact of code changes or when analyzing behavior that might not be present or easy to isolate in a production environment captured by continuous profiling. Use cases where local profiling shines, and continuous profiling might be less helpful or slower, include: debugging performance regressions introduced in a specific feature branch before merging, interactively testing different optimization ideas for a known bottleneck, or analyzing issues that only manifest in specific development or testing environments.

💡 Tip: Enabling the

pprofendpoint in production-like environments (perhaps on a specific instance, canary, or behind authentication) can be invaluable for quick troubleshooting of live issues.

The easiest way to enable this is via a side effect import of net/http/pprof.

package main

import (

"log"

"net/http"

// Import pprof package for side effects: registers HTTP handlers.

// We use the blank identifier _ because we only need the side effects (handler registration)

// from its init() function, not any functions directly from the package.

_ "net/http/pprof"

)

func main() {

// Start the pprof HTTP server on a separate port and goroutine.

// Running it in a separate goroutine ensures it doesn't block the main application logic.

// Using a different port (e.g., 6060) is common practice to avoid interfering

// with the main application's port (e.g., 8080).

go func() {

log.Println("Starting pprof server on localhost:6060")

log.Println(http.ListenAndServe("localhost:6060", nil))

}()

// Your main service logic would go here...

// For demonstration, we'll just block forever.

log.Println("Main application running...")

select {}

}This import registers several endpoints under /debug/pprof/ on port 6060:

/debug/pprof/profile: CPU profile (collects data for a duration, typically 30s by default)./debug/pprof/heap: Memory profile (snapshot of heap allocations)./debug/pprof/goroutine: Goroutine profile (stack traces of all current goroutines)./debug/pprof/block: Block profile (stack traces leading to blocking sync primitives)./debug/pprof/mutex: Mutex profile (stack traces of contended mutex holders).

Once your service is running, you can analyze these profiles using the go tool pprof command. The most convenient way is often using the -http flag, which fetches the profile data and launches an interactive web UI:

# Analyze CPU profile (will collect data for 30s)

go tool pprof -http=:9090 localhost:6060/debug/pprof/profile

# Analyze memory profile (instantaneous snapshot)

go tool pprof -http=:9090 localhost:6060/debug/pprof/heap

Running these commands will fetch the profile data from your running application and open a web browser interface served on port 9090, allowing you to explore the data visually.

💡 Tip: If profiling reveals significant time spent in standard library functions (like marshalling/unmarshalling or compression), consider evaluating high-performance third-party alternatives (e.g.,

sonicfor JSON). Always benchmark to confirm improvements in your specific use case.

Understanding Flame Graphs #

One of the most powerful visualizations in the pprof web UI is the flame graph. Below is an interactive flame graph generated from a simple Go program designed to highlight CPU usage and allocation patterns. You can find the source code for this example in the /examples/flamegraph directory and play with full version here.

Flame graphs visualize hierarchical data (like call stacks) effectively. Key things to understand when reading any flame graph:

- Y-axis: Represents the stack depth (function calls), with the root function (

main) typically at the bottom and deeper calls stacked on top. - X-axis: Spans the sample population. The width of a function block indicates the proportion of time (for CPU profiles) or allocated memory (for heap profiles) spent directly in that function or functions it called. Wider blocks mean more time/memory consumption relative to the total profile duration or allocation size.

- Reading: Look for wide plateaus, especially near the top of the graph. These represent functions where significant time is being spent directly. Clicking on a block zooms in on that part of the hierarchy, filtering the view to show only that function and its descendants.

The pprof UI also offers other views like Top (tabular list of most expensive functions), Graph (call graph visualization - requires Graphviz), and Source (line-by-line annotation).

⚠️ You need

graphvizinstalled locally for some visualization options (like the ‘Graph’ view) within the web UI. You can install it running:brew install graphvizor check https://graphviz.org/download/

Benchmarking Specific Functions with go test

#

While profiling helps you find bottlenecks in your running application, sometimes you want to measure the performance of a specific piece of code in isolation or compare different implementations of a function. Go has excellent built-in support for this via its testing package, which includes benchmarking capabilities.

Benchmarks live in _test.go files alongside your regular tests. They look similar to tests but follow the BenchmarkXxx naming convention and accept a *testing.B parameter.

Here’s a simple example: Suppose we have a function ConcatenateStrings:

package main

import "strings"

func ConcatenateStrings(parts []string) string {

return strings.Join(parts, "")

}

// Slower implementation for comparison:

func ConcatenateStringsSlowly(parts []string) string {

var result string

for _, s := range parts {

result += s

}

return result

}We can write benchmarks for these in concat_test.go:

package main

import "testing"

var input = []string{"a", "b", "c", "d", "e", "f", "g", "h", "i", "j"}

func BenchmarkConcatenateStrings(b *testing.B) {

// The loop runs b.N times. b.N is adjusted by the testing framework

// until the benchmark runs for a stable, measurable duration.

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

ConcatenateStrings(input)

}

}

func BenchmarkConcatenateStringsSlowly(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

ConcatenateStringsSlowly(input)

}

}You run benchmarks using the go test command with the -bench flag. The . argument tells it to benchmark functions in the current folder:

# Run all benchmarks in the current folder

go test -bench=.

# Add memory allocation stats

go test -bench=. -benchmem

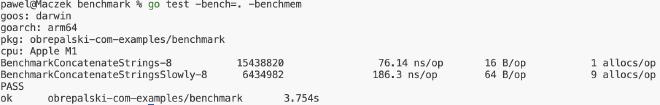

The results clearly show that ConcatenateStrings is not only ~2.5x faster (186 vs 73 ns) but also results in less memory allocations (1 vs 9):

Benchmarking is invaluable for:

- Validating the performance impact of code changes before merging.

- Comparing performance of different algorithms/libraries.

- Micro-optimizing critical functions identified through profiling.

Beyond timing and allocations, Go also offers execution tracing specifically during tests via go test -trace=trace.out. This generates a trace file that can be visualized with go tool trace trace.out. The visualization provides a detailed timeline showing goroutine execution, points where goroutines block (e.g., on syscalls, channels, mutexes), and garbage collection events, which is invaluable for diagnosing concurrency issues or unexpected latency within a test run.

💡 Tip: You can generate CPU and memory profiles specifically for your benchmark execution using flags like -cpuprofile cpu.prof and -memprofile mem.prof. This lets you use pprof to analyze the performance characteristics of the exact code exercised by the benchmark.

For more details, see the official Go documentation on writing benchmarks and tracing.

Continuous Profiling: Performance Insights from Production #

While local profiling is great for development and debugging specific issues, continuous profiling captures data from your live production environment over time. This provides invaluable insights into real-world performance, helps catch regressions early, and allows comparison across deployments.

Benefits:

- Understand performance under actual production load and traffic patterns.

- Easily compare performance between versions (e.g., canary vs. stable).

- Quickly identify performance regressions introduced by new code.

- Low overhead; profiles are collected periodically across deployments.

- Available on most major cloud providers and as third-party solutions.

- Optimize Resource Utilization: Identify trends in CPU and memory usage under real load across different versions, helping pinpoint inefficiencies or regressions that impact infrastructure costs. Continuous profiling is extremely useful here as it shows actual resource consumption patterns over time, not just theoretical or benchmarked behavior.

Google Cloud Profiler Example #

Cloud Profiler makes it easy to get started with continuous profiling on Google Cloud. It allows version-to-version comparisons, which is perfect for analyzing the impact of a new deployment.

⚠️ Ensure the service account your application runs under has the

roles/cloudprofiler.agentIAM role to submit profiles.

Integrating the profiler is straightforward:

package main

import (

"log"

"os"

"cloud.google.com/go/profiler"

)

func main() {

// Configuration for the profiler.

cfg := profiler.Config{

Service: "your-service-name", // Replace with your service name

ServiceVersion: os.Getenv("APP_VERSION"), // Use an env var for version (e.g., BUILD_ID, git SHA)

// ProjectID is optional if running on GCP infra (inferred)

// ProjectID: "your-gcp-project-id",

}

// Start the profiler. Errors are logged if it fails to start.

if err := profiler.Start(cfg); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("WARN: Failed to start profiler: %v", err)

// Usually, you wouldn't stop the app if the profiler fails,

// so we just log the error.

}

// ... rest of your application startup and logic ...

log.Println("Application started...")

}💡 Tip: Using an environment variable like

APP_VERSION(populated from your CI/CD system with a build ID or git commit hash) is highly recommended. This allows Cloud Profiler (and other tools) to correlate performance data directly with specific code versions, making it easy to track regressions or improvements over time.

For more details, refer to the Google Cloud Profiler Go setup documentation.

Other Profiling Solutions #

Most major cloud providers offer profiling tools, though language support varies (e.g., AWS CodeGuru for Java/Python, Azure Monitor for .NET). There are also excellent third-party, language-agnostic observability platforms that include continuous profiling, such as Datadog, New Relic, Honeycomb, and Grafana Pyroscope.

Profile-Guided Optimization (PGO): Letting Profiles Drive Compilation #

Continuous profiling gives us insights into production behavior. What if we could feed those insights back into the compiler? Since Go 1.21, the compiler includes built-in support for Profile-Guided Optimization (PGO), which is enabled by default. PGO uses CPU profiles gathered from real-world application runs to make more informed optimization decisions during the build process.

The core idea is simple: if the compiler knows which parts of your code are executed most frequently (the “hot paths” identified in a CPU profile), it can apply more aggressive optimizations to those specific areas. A primary example of such optimization is improved inlining – deciding more accurately when replacing a function call with the body of the called function will yield the best performance based on actual usage patterns.

Getting Started with PGO #

Leveraging PGO can be straightforward:

- Obtain a Profile: Collect a representative CPU profile (in the standard

pprofformat) from your application running under a realistic production or staging load. The continuous profiling tools mentioned earlier are excellent sources for this. - Place the Profile: Copy the collected profile file (e.g.,

cpu.pprof) into the root directory of your main package (where your main.go file typically resides) and rename it to default.pgo. - Build: Simply run go build. The Go compiler (1.21+) automatically detects default.pgo in the main package directory and uses it to guide optimizations.

You can also explicitly specify a profile location using the -pgo flag during the build (go build -pgo=/path/to/your/profile.pprof) or disable PGO entirely (go build -pgo=off).

Benefits and Considerations #

PGO offers the potential for performance improvements by fine-tuning the compiled code based on actual execution data. However, based on practical experience and the nature of PGO, keep these points in mind:

- Performance Gains: While the Go team often reports gains in the 2-7% range for typical CPU-bound benchmarks, your results will vary based on your workload. Services that are heavily I/O-bound (spending most of their time waiting for network or disk) might see less significant gains compared to CPU-bound services where computation is the bottleneck.

- Increased Build Times: Enabling PGO often significantly increases build times (potentially by 5-10x or more in some cases). This happens because the profile information can influence how dependencies are compiled, often forcing them to be rebuilt. Implementing robust build caching in your CI/CD pipeline is highly recommended to mitigate this impact.

- Measure Impact: Always benchmark your application with and without PGO enabled to objectively measure the performance difference in your specific context. Compare the gains against the added build complexity.

- Evolving Feature: PGO is a relatively new addition to the Go toolchain and is expected to improve and offer more sophisticated optimizations in future Go releases.

PGO represents a fascinating link between runtime observability and compile-time optimization, offering another lever to pull in the quest for better Go service performance, especially when combined with insights from continuous profiling.

🔗 For more detailed information, refer to the official Go documentation on Profile-Guided Optimization.

A Brief Word on Tracing #

Metrics give you the overview (the “what”), and profiling gives you the deep dive into a single service’s internals (the “why” for CPU/memory). But what about understanding the sequence and duration of operations within a request’s lifecycle? If a specific API endpoint is slow, is it the database query, an external API call, or the internal processing logic that’s taking the most time?

This is where Tracing comes in. At its core, tracing provides a detailed view of a request or operation’s journey through your system by breaking it down into timed steps called spans. Even within a single service, tracing can be incredibly useful for pinpointing bottlenecks in complex workflows. For example, you could trace a single incoming request to see how much time was spent in authentication middleware, data fetching, data transformation, and response serialization.

Now, consider the microservices environment. If a user request is slow, and it involves calls chaining across multiple services, identifying the culprit becomes much harder using only metrics and profiles from individual services. This is the problem Distributed Tracing solves. It involves propagating context (like a unique trace ID) with requests as they move between services, allowing you to visualize the entire end-to-end journey, including timing for each service hop and the operations within those services.

Implementing tracing often involves instrumenting your code (manually or automatically) to create these spans. OpenTelemetry is the emerging standard for observability data, including tracing.

Auto-instrumentation Challenge in Go: Unlike runtime-interpreted languages like Java or Python, Go compiles directly to native machine code. This makes automatic instrumentation (where an agent modifies code at runtime to inject tracing logic) much harder. While OpenTelemetry provides libraries for manual instrumentation in Go, true auto-instrumentation often relies on techniques like:

- Compile-time code generation.

- Using eBPF in the Linux kernel to observe application behavior (like system calls, network requests) without modifying the application code itself. eBPF-based auto-instrumentation for Go is an active area of development in the observability space.

While powerful, setting up distributed tracing is often more involved than metrics or profiling. However, understanding its role completes the picture of modern observability. For many optimization tasks focused within a single service, metrics and profiling are the essential starting points.

Conclusion #

Optimizing Go microservices effectively starts with visibility. This post focused on the foundational pillars for observing your application’s behavior:

- Begin with metrics (using Prometheus) to get a high-level, quantitative view of your service’s health, resource consumption, and request handling (latency, errors, rate). This allows you to monitor trends and set alerts.

- When metrics indicate a problem (e.g., high latency, excessive CPU/memory usage) or you need to proactively optimize, dive deeper with profiling (using

pproflocally or a continuous profiler like Google Cloud Profiler in production). This reveals exactly where CPU time is spent and memory is allocated within your code. - Leverage the collected CPU profiles further with Profile-Guided Optimization (PGO), allowing the compiler to make more informed optimization decisions (like inlining) based on real-world execution data, potentially improving performance with no code changes.

Armed with the metrics and profiling techniques discussed here, you can already take concrete actions to improve your service’s performance and efficiency directly within your application code. For instance, you can:

- Refactor CPU-intensive functions identified via CPU profiling.

- Optimize memory usage and eliminate leaks identified via heap profiles.

- Identify and potentially remove unnecessary work revealed in CPU profiles.

- Benefit from compiler optimizations targeted at your actual hot paths via PGO.

- Use latency distribution metrics (like histograms or summaries) to set meaningful Service Level Objectives (SLOs) and track improvements.

- Analyze process/runtime metrics to understand baseline resource usage and GC behavior before and after code changes.

These tools primarily help you understand and optimize your application code. In the next post, we will shift focus and explore how tuning the Go runtime itself can provide further performance gains, building upon the application-level insights gained here.

Further Reading #

- Prometheus Documentation - Learn more about Prometheus.

- Profiling Go Programs - Official Go blog post on

pprof. - Go Flamegraph Playground - Run simple Go programs and see how their flamegraphs in your browser

- What is continuous profiling? - CNCF article explaining the concept.

- Profile-guided optimization - Official documentation.

- OpenTelemetry Go Documentation - For manual instrumentation and understanding tracing concepts in Go.